From Banding to Brushstrokes: How Bird Observation Inspires My Artwork

A Weekend of Bird Banding at Bill and Jan’s

I’ve never enjoyed the cold; I prefer basking in the sun like a softshell turtle on the riverbank in the dead heat of summer. But if you want to experience bird banding at Bill and Jan’s, you have to deal with frozen fingers. I’ve made many trips to their house to participate in bird banding (mostly in March and April), and each trip is just as exciting as the previous. I want to clarify that I do not retrieve birds from nets, nor do I band them. I only assist in releasing birds, as you must be a licensed bird bander to retrieve and band birds.

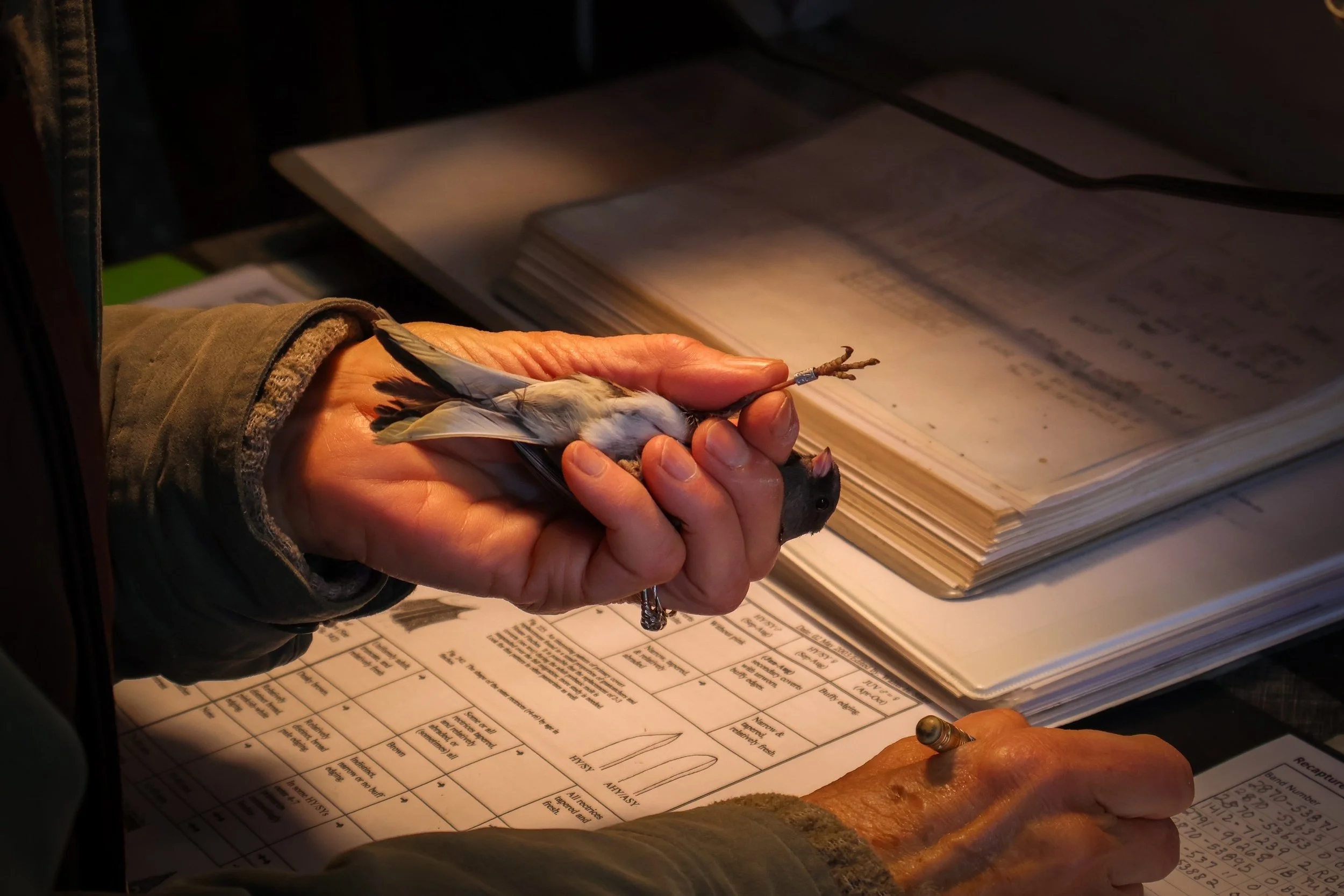

Bill holds a male purple finch while Jan holds a female purple finch.

Every bird banding excursion is different; some days are filled with American goldfinches (I think over eighty were banded on one trip), other days have a variety of species, and some days only a handful are banded. On this trip, I was beyond excited to see my first-ever purple finch. To many, the purple finch and the house finch look the same; however, through an artist’s eyes, there are many differences. Purple finches are a deeper cherry color, whereas house finches appear more orangey-red like raspberries. The purple finches are also stockier with a bulkier bill. While they appear similar, these features make all the difference in a painting. As someone who considers themself an artist first and then an avid nature nerd (one day I'll be a naturalist), I’m always observing. Always looking for the details, patterns, and nuances of my subject to better understand them as well as interpret them with brush and paint. Bird banding has both inspired my artwork and instilled a desire to protect the very animals that I love to paint.

Why Bird Banding Matters

Bird banding is a technique used to track and identify birds. Mist nets are used to trap the birds, which are then gently removed to begin the banding process. First, the bird’s wings and tail feathers are measured to determine age and sex, though some species are visually easier to identify male vs. female (think northern cardinals and American goldfinches) while others must be measured. This information is then recorded in a book that will later be submitted to the Bird Banding Laboratory at the Pautuxent Wildlife Refuge. Next, the bird will receive a small, silver band with a unique nine-digit number. Special pliers are used to attach the ring to the bird’s leg. Fear not! These rings slide easily along the bird’s leg, so they won’t hurt them or interfere with daily life. Once data is recorded and the bird is banded, they are released back into the wild. From personal experience, I can tell you that the birds don’t seem bothered by being handled, banded, and then released. They go on about their day as if nothing happened. However, there is one exception. Tufted titmice always seem inconvenienced and will curse at you (according to Jan, and she is absolutely correct) for disrupting their morning.

Bird banding contributes significantly to our understanding of avian populations and their behavior, making it an important technique to study birds. By attaching lightweight bands to the legs of birds, researchers can track individual movements, migration patterns, and survival rates over time. This data helps identify trends in population decline, informing conservation strategies and habitat protection efforts. Additionally, bird banding encourages studies on the effects of environmental changes and human activities on bird populations to deepen our knowledge of a healthy ecosystem and biodiversity.

“If you can make people love something, they’ll want to protect it.”

After many trips to Bill and Jan’s to assist in birding, I learned that bird banding also offers individuals a chance to see birds up close, which I think strengthens their appreciation for birds. There’s something very special about holding a wild creature in your hands; I wish I could put into words how it feels to hold the animals I love to paint, but the best way I can describe it is truly a sense of wonder. Both Bill and Jan always say that if you can make someone learn to love something, they’ll want to protect it. By allowing people to experience birds in hand, Bill and Jan hope to instill a love and appreciation for birds and their habitats—and I believe they’re doing just that.

Interested in learning more about birds? Check out Bill’s blog!

The Intersection of Art and Nature

Birds provide a rich source of visual inspiration, and bird banding offers the perfect opportunity to document and observe the beauty and intricacy of birds, from their feather patterns and colors to their individual personalities.

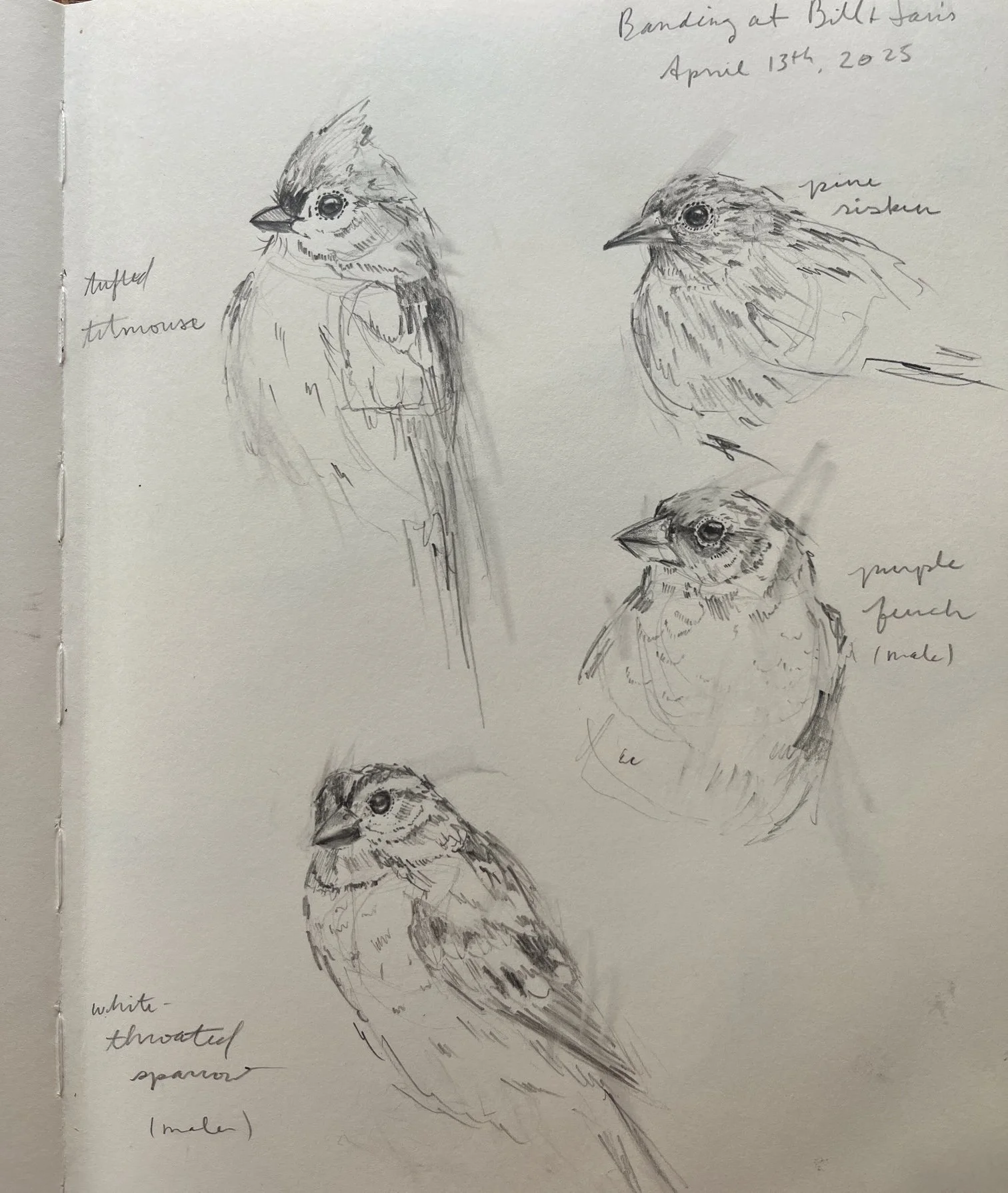

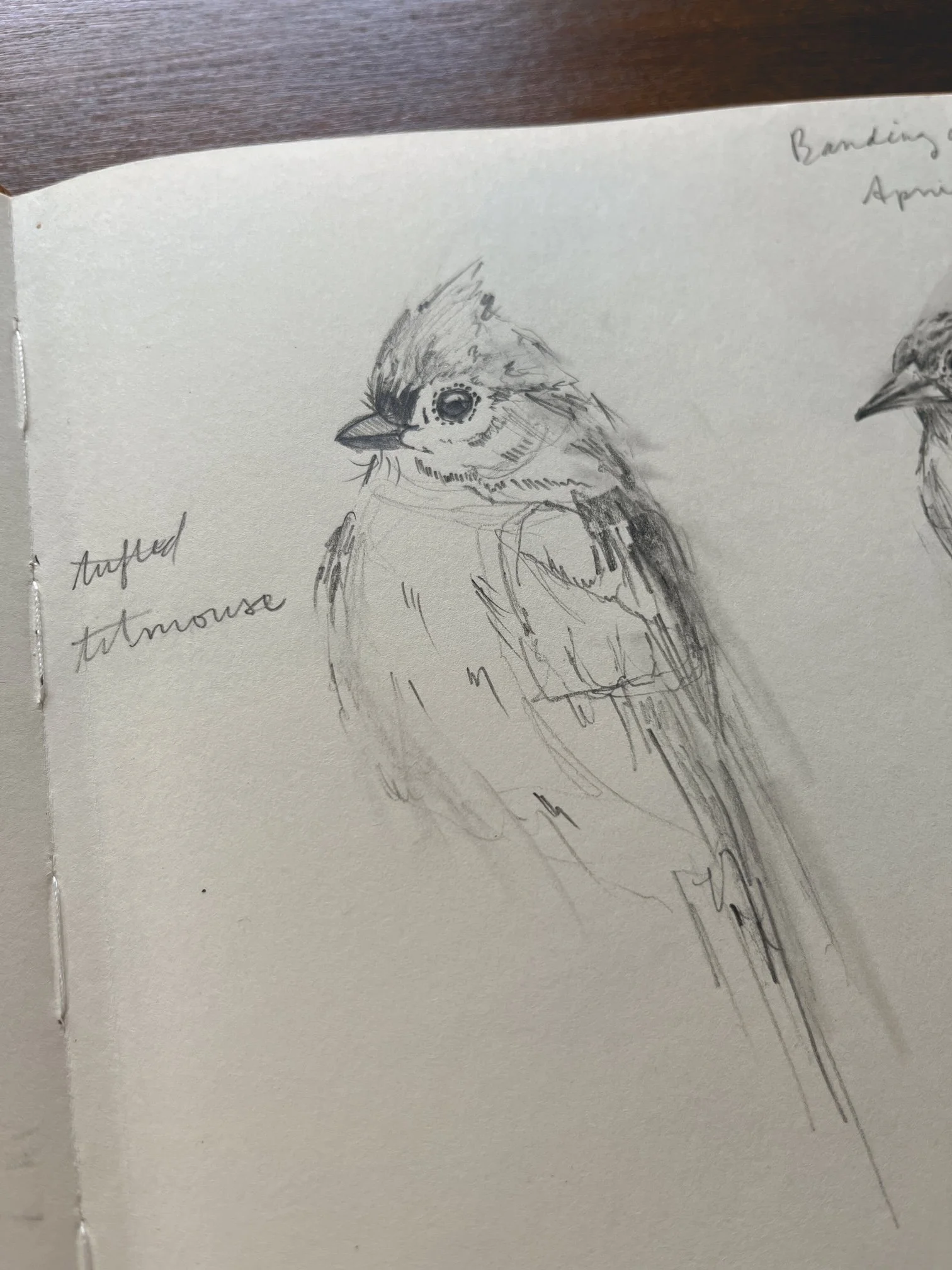

One of my favorite ways of exploring birds through art is by sketching them from my photos and from life (even if they look wonky). I spent most of this bird banding excursion jotting down notes on the species banded; I did manage to take a handful of reference photos to sketch later in my sketchbook. These sketches help me understand bird anatomy, which is integral for my painting process, as I do not use a preliminary sketch when painting. Observing birds in hand allows me to see all the intricate feather details as well as features unique to each bird. While I don’t often paint every single feather, it does help me understand how birds should look in my artwork.

Most days, I observe birds in the wild and at my feeders. While this form of observation is helpful for my artwork, studying birds in hand unlocks all the tiny details I wouldn’t see from a distance. I loved seeing the tufted titmouse up close; they have beautiful, delicate feathers and dark eyelash-like feathers beneath their beaks. This is a small detail that might go unnoticed in my art--until now!

Bird banding also provides me the opportunity to hold birds and better understand their shape and size compared to other species. For instance, American goldfinches are much smaller than I initially believed—they’re smaller than tufted titmice! Carolina wrens lack a neck (ok, they have necks, but they’re hard to find compared to other birds) and feel rounder, almost like a golf ball, while downy woodpeckers have a slightly elongated body. These details may seem insignificant, but I do enjoy painting birds as accurately as possible, even in my loose style.

Birds aren’t my only source of inspiration for painting; I also love creating floral artworks and depicting other wild animals native to Appalachia. My surroundings, nature hikes, and the visitors at my feeders heavily influence my work. My environment has truly shaped the artist I’ve become, and I believe that art and nature share more in common than we often realize. The elements of art are woven throughout nature: the variety of feather colors, the shapes of leaves, and the textures of stones along the crick (creek if you’re not from around here). Nature offers endless inspiration for artists—you just have to step outside.

Sketches in both watercolor and pencil from my day of bird banding.

I hope you enjoyed this post and found a little inspiration along the way.

Happy Birding & Painting!